Iza Ali’s five children are still waiting for their first meal at 3 p.m. It’s not the first time the family has gone hungry since fleeing extremist violence in northeast Nigeria six years ago.

She and her husband manage to earn about $3 a day, but it’s rarely enough to feed their family of seven. Often, they forage for wild greens near the Jere displacement camp on the outskirts of Maiduguri.

“When we can’t find food, we just drink water,” says the 25-year-old mother, holding her 4-month-old baby. “Only God can help us now.”

Humanitarian groups are raising alarms as families like Ali’s face worsening hunger due to poor food production in Nigeria and global aid resources being redirected because of the war in Ukraine.

Severe malnutrition in children in northeast Nigeria has surged from affecting 1.4 million to 1.7 million kids in the past year, according to Priscilla Bayo Nicholas, a nutrition expert with UNICEF in Borno state. Back in 2017, the number was only 400,000.

“If we don’t treat them, these children won’t survive,” she warned.

Many, like Ali, have lost their livelihoods since 2009, when extremist violence erupted in Nigeria. Groups like Boko Haram and the Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP) have caused the deaths of over 35,000 people in Nigeria and neighboring countries like Chad, Niger, and Cameroon. At least 2.1 million people have been displaced, according to the UN.

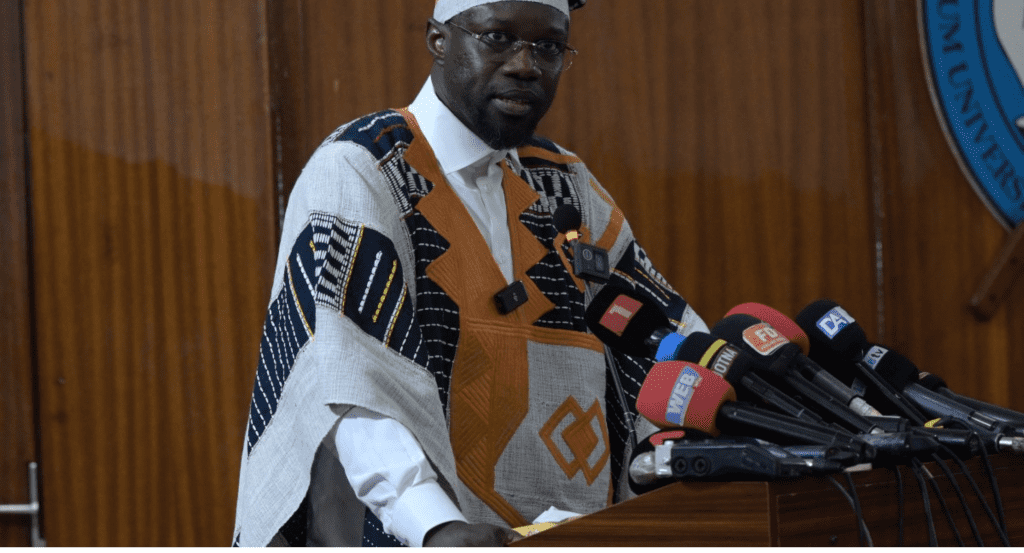

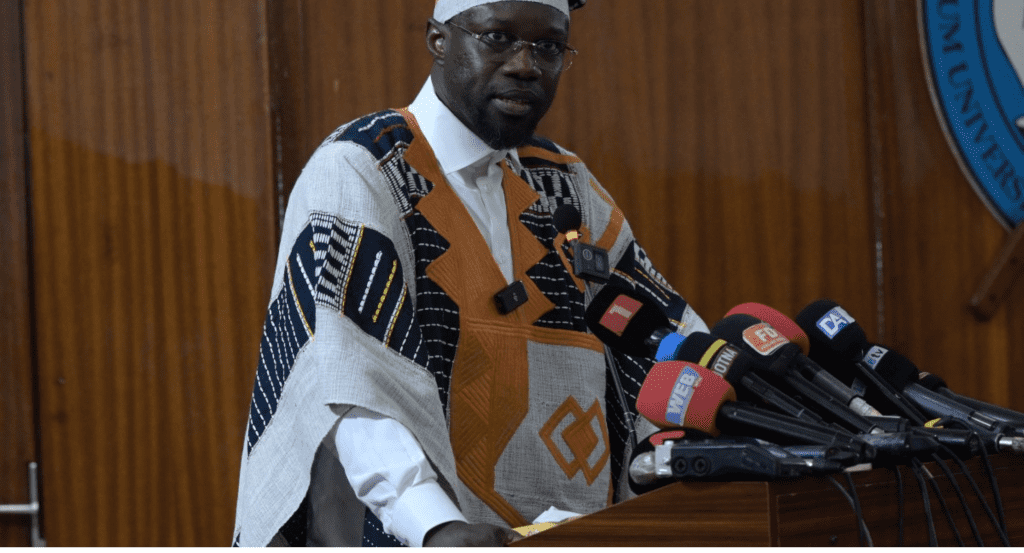

During a recent visit to Maiduguri, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres met with displaced Nigerians as part of a “solidarity visit” to the victims of terrorism. He called for an extra $351 million to support the UN’s humanitarian efforts in Nigeria, which require $1.1 billion in total.

However, many displaced people say their hope is fading.

In the Banki displacement camp near the Cameroon border, over 50,000 people displaced by violence are being cared for by UN workers. The camp is guarded by heavily armed soldiers and filled with women and children whose future remains uncertain.

Inside the camp’s nutrition center, children with severe malnutrition lie on beds as their mothers watch over them. One 20-month-old boy named Mbolena rubs his swollen belly, and his mother, Isa Ali, is relieved to see him feeling a bit better. Meanwhile, Maryam Hassan holds her severely injured baby close as the child fights for survival.

Many children remain trapped in areas too dangerous for aid workers to reach, due to ongoing violence, Nicholas explained.

Gomezgani Jenda from Save the Children’s Nigeria office said that the conflict worsens the already dire situation for children in the region.

“The humanitarian crisis affecting children is now greater than ever,” Jenda said.

In many Nigerian displacement camps, the government provides food while aid organizations focus on education and healthcare. However, the food provided by the Nigerian relief agency is often gone within a few days, said Mala Bukar, head of the Jere camp.

Nigerian authorities have begun shutting down some camps in an effort to return people to their original homes, as President Muhammadu Buhari claims the war is “coming to an end.” More than 50,000 Islamic militants have reportedly surrendered, according to the Nigerian military, though the International Crisis Group warns that ISWAP is expanding its control in rural Borno state.

Ali dreams of returning home to farm, but the constant threat of violence keeps her from leaving the camp.

“We want to go back,” she said. “But only if the land is cleared and there are no Boko Haram fighters to harm us.”