Uganda has initiated legal proceedings to evict landowners who are blocking the development of a major regional oil pipeline, known as the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP). This project is crucial for transporting crude oil from Uganda’s oil fields in the Lake Albert region to the Tanzanian coast for export.

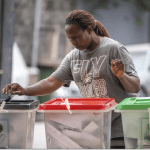

However, the pipeline’s construction has faced resistance from some landowners, who have refused to vacate their properties. Many of these landowners claim they were not adequately compensated or given fair treatment by the government or the project’s developers. In response, Uganda’s government is taking legal action to force their removal and allow the project to proceed.

EACOP is a $3.5 billion project and a significant part of Uganda’s oil strategy, designed to boost the country’s oil exports and overall economic growth. While the government asserts that the project is vital for development, environmental groups and local communities have raised concerns about the potential ecological damage and displacement caused by the pipeline.

The legal move by the Ugandan government highlights the tension between economic development and land rights, with many questioning whether the pipeline’s benefits outweigh its social and environmental costs. If completed, EACOP will be the longest heated crude oil pipeline in the world, spanning approximately 1,443 kilometers.

This case underlines the complex balance between progress, economic goals, and the rights of local populations in Africa’s emerging oil sector.

Uganda’s decision to sue landowners standing in the way of the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) has intensified the conflict surrounding the massive regional project. The $3.5 billion pipeline, which stretches 1,443 kilometers, is designed to transport crude oil from Uganda’s Lake Albert oil fields to the Tanzanian coast for export. This project promises to significantly boost Uganda’s oil exports and stimulate economic growth in both Uganda and Tanzania.

However, the project has faced significant resistance from landowners, many of whom argue that they have not been fairly compensated for their land. Some claim that the compensation offered is inadequate, delayed, or insufficient to cover the loss of their property and livelihood. Despite this, the Ugandan government has insisted that the pipeline is a key infrastructure project necessary for national development and is now resorting to legal measures to forcibly evict those who refuse to move.

The pipeline project has also drawn criticism from environmentalists and human rights groups, both locally and internationally. Concerns have been raised over the environmental impact, including threats to wildlife and natural reserves, as well as potential displacement of communities along the pipeline route. Activists argue that the economic benefits of the project may not be evenly distributed, with rural and vulnerable communities bearing the brunt of the negative consequences.

This legal battle underscores the broader tension between economic development and the protection of land rights, environmental sustainability, and community well-being. The outcome of Uganda’s lawsuit against the landowners will likely set a precedent for how future infrastructure projects are handled in the region. The case is being closely watched by stakeholders across Africa and beyond, as it highlights the challenges faced in balancing industrial progress with the rights of citizens and the environment.