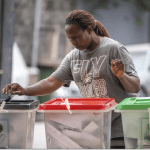

After leaving her abusive husband, Milla Nemoudji faced many struggles due to the male-dominated land system in southern Chad. Without her husband, Milla found it hard to survive in a society where men usually control access to land. Even though she grew up in a farming family, she could not easily secure land to work on.

Divorce is uncommon in Chad, and support for women like Milla is rare. To earn a living, she sold fruits and worked as a field laborer during the rainy season. But everything changed when a women’s collective came to her village last year. Milla joined the group, which allowed her to gain access to land for the first time. She started growing cotton, peanuts, and sesame, which gave her enough money to meet her basic needs.

Milla’s village, Birman, is located near Moundou, Chad’s second-largest city, in an area where many people live off farming. Although women do most of the farm work, they often don’t have control over the land. Traditionally, village chiefs manage land access and require annual payments from farmers. Women are usually excluded from owning or inheriting land, which forces them to rely on male relatives and keeps them in a lower social position.

Chad’s land rights system is further complicated by the coexistence of traditional laws and statutory laws. Although new laws allow any citizen to own land, these laws are not consistently enforced, especially in rural areas. This makes it harder for women like Milla to assert their rights, and the response from the community can be negative.

“There’s no one to help you, even though everyone sees your suffering,” Milla told the Associated Press. She criticized the traditional land system and urged local leaders to take domestic violence more seriously. “If women had better access to land, they wouldn’t have to stay with abusive husbands.”

Initiatives like N-Bio Solutions, the collective Milla joined, are challenging these norms. The collective, founded in 2018 by Adèle Noudjilembaye, an agriculturist and activist from a nearby village, negotiates with traditional chiefs to find land for women. So far, Noudjilembaye has organized five collectives, each with around 25 members. While these efforts are gaining attention, they are still limited by financial constraints, and some women fear losing what little they have.

Noudjilembaye explained that many women stay in abusive situations due to financial dependence, fear of being judged by society, or lack of support.

These collectives not only empower women but also promote sustainable farming practices like crop rotation, organic farming, and using drought-resistant seeds. According to the United Nations, women with access to land and resources are more likely to use these sustainable methods, which can boost local food production.

However, life remains difficult for women who try to stand up for their rights. Chad ranks 144th out of 146 countries in the Global Gender Gap Index, and maternal mortality is very high, with 1,063 deaths per 100,000 births—three times the global average. Only 20% of young women in the country can read and write.

Milla’s family supported her emotionally after she left her husband, but they did little to confront her abuser or seek justice for her. “The system failed me when I asked for help after my husband burned down my house,” she said. When she reported the incident to the village chief, “nothing was done to resolve my problem.”

Village chief Marie Djetoyom, who holds a hereditary role, admitted that she was afraid to take action because she feared retaliation. She felt constrained by the traditional laws governing land rights.

Despite the lack of support from local leaders, the women in Birman have found strength through the collective. “Since cultural norms make it hard for women to access land on their own, the community-based approach is the best option,” said Innocent Bename, a researcher at a local research center.

Another woman, Marie Depaque, who struggled after her second husband refused to support her children from a previous marriage, added, “Our fight for land rights isn’t just about making a living; it’s about justice, equality, and the hope for a better future.”

Milla now dreams of better education for the children in her village so they can escape the cycle of poverty and violence. She advocates for changes to the land ownership system and encourages others to stand up for their rights.

“Knowing my rights means I can ask for help from the authorities and demand justice,” Milla said.