BANJUL, The Gambia — Nearly a decade after the fall of former ruler Yahya Jammeh, survivors of his 22-year regime say financial compensation alone cannot heal the wounds of torture, killings and repression. For many, “real justice” remains elusive.

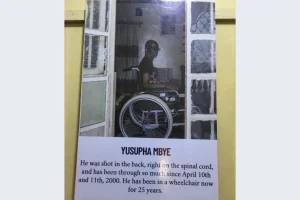

In Kanifing, about 11 kilometres from the capital Banjul, 42-year-old Yusupha Mbye sits in a wheelchair — a reminder of the April 2000 student protests when paramilitary officers opened fire on demonstrators. At least 14 people were killed during the crackdown.

Mbye was 17 when a bullet shattered his spinal cord, leaving him permanently paralysed.

“I cannot do anything for myself without the help of my family,” he said, describing years of depression and dependence. His father, who supported him until his death in 2013, had hoped to see Jammeh prosecuted. “He died without seeing that,” Mbye said.

His ageing mother now fears she too may not live long enough to witness accountability.

Reckoning with a painful past

Jammeh ruled The Gambia from 1994 to 2017 after seizing power in a coup. His government was later accused of widespread abuses, including extrajudicial killings, torture, sexual violence and enforced disappearances.

After Jammeh fled into exile in Equatorial Guinea in 2017, the government established the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC) to investigate crimes committed during his tenure. The commission documented thousands of violations, named perpetrators and recommended reparations and criminal prosecutions.

To implement compensation payments, authorities created the Reparations Commission, which recently began phased payments to victims of abuses committed between 1994 and 2017. The government has allocated 40 million dalasi (about $550,000) over five years for the programme.

But survivors say money cannot substitute for accountability.

“We want justice, not just money”

Mamudou Sillah’s brother, Cadet Amadou Sillah, was among nearly two dozen soldiers executed in November 1994 after being accused of plotting a coup. The TRRC later concluded he was not involved and had been scapegoated.

“Thirty-two years later, our wounds are as fresh as if it happened yesterday,” Sillah said.

Although his family received 600,000 dalasi ($8,170) in compensation, he insists it does not replace justice. “We want Jammeh and everyone responsible for my brother’s murder to face it,” he said.

Similarly, Mbye returned an earlier interim payment of 19,000 dalasi ($259), saying it did not address his urgent medical needs. He requires specialised spinal surgery and says promises made by President Adama Barrow to cover survivors’ treatment have yet to materialise.

“I needed medical treatment, not cash,” Mbye said.

Justice delayed, justice denied?

Human rights advocates warn that delays risk denying victims closure. The Gambia Center for Victims of Human Rights Violations says more than a dozen Jammeh-era victims have died while awaiting justice.

High-profile cases — including that of opposition figure Ebrima Solo Sandeng and activist Femi Peters — underscore the long wait many families have endured.

While Jammeh remains in exile in Equatorial Guinea, efforts to prosecute him are gathering pace. In 2024, The Gambia passed legislation establishing a Special Prosecutor’s Office and Special Accountability Mechanisms. With backing from Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), plans are underway for a hybrid Special Tribunal comprising Gambian and international judges to try alleged perpetrators, including Jammeh, if he returns.

International courts have also acted. Switzerland convicted former interior minister Ousman Sonko in 2023, while courts in Germany and the United States have sentenced members of Jammeh’s paramilitary unit, known as the Junglers.

Still, for many survivors, progress feels slow.

According to the Reparations Commission, 1,009 victims were identified as eligible for compensation. So far, 248 have been fully compensated, while 707 have received partial payments.

For families like the Sillahs, closure remains incomplete. The remains of executed soldiers exhumed in 2019 are still being held in a Banjul morgue pending use in future tribunal proceedings.

“We want to bury our brother properly,” Sillah said. “We want closure.”

As The Gambia continues its fragile transition from dictatorship to democracy, survivors say the country must move beyond symbolic gestures.

“People keep saying justice is coming,” Mbye said quietly as his mother wheeled him indoors at dusk. “But will it ever arrive?”