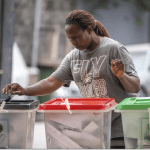

Togo’s presidency has requested a “second reading” of a contentious constitutional reform following public protests. Critics say the reform is a strategy by President Faure Gnassingbé to extend his nearly two-decade rule and avoid direct presidential elections.

In a statement released on Friday, Gnassingbé’s office justified the review by citing public interest generated by the reform since its adoption last week. The reform, initially approved with 89 votes in favor, one against, and one abstention, proposes that parliament elect the president, removing the need for direct presidential elections.

Given that Gnassingbé’s party controls parliament, the reform raises the likelihood that he would remain in power after the 2025 presidential election.

A Move to Evade Voters

Opposition leaders, including Brigitte Adjamagbo-Johnson of the Democratic Convention of the African People (CDPA), criticized the reform as an attempt to avoid facing voters.

“This change is being made because the ruling party knows it can no longer cheat in presidential elections,” Adjamagbo-Johnson told RFI.

“Gnassingbé has never been genuinely elected, and he knows that people are waiting to vote him out in the next election.”

Gnassingbé came to power in 2005 following the death of his father, Gnassingbé Eyadéma, who ruled for 38 years after seizing power in a 1967 military coup. Despite widespread protests in 2017 and 2018 against his extended rule, Gnassingbé survived the demonstrations through crackdowns and internet shutdowns. In 2019, a constitutional amendment was passed that could allow him to stay in power until 2030.

Constitutional Reform: Parliamentary System

The proposed reform would introduce a parliamentary system that limits the president’s powers. Under the new system, the presidency would become a largely ceremonial role with a single six-year term. The real power would reside with the “President of the Council of Ministers,” similar to a Prime Minister. This position would be held by the leader of the majority party or coalition following legislative elections.

Adjamagbo-Johnson expressed doubts about the reform, noting that while parliamentary systems work elsewhere, Togo’s context makes it unlikely to succeed.

“We are dealing with a government resistant to democracy and committed to blocking political change,” she said. “This is not a genuine shift but a diversion to keep power indefinitely.”

Uncertainty Around Implementation

The parliamentary and regional elections are scheduled for April 20, 2024, and the opposition is preparing to participate after boycotting the 2018 elections. However, it remains unclear when lawmakers will begin the second reading of the constitutional reform or if any amendments will be added.

The government has also not communicated when the new constitutional changes would take effect. Observers fear the reforms could further erode trust in Togo’s political system, where elections have long been criticized as lacking transparency.

As Togo transitions toward its fifth republic, questions remain about whether this shift will lead to genuine democratic reform or simply entrench Gnassingbé’s hold on power.