In a quiet room at the Ahmed Baba Institute in Timbuktu, history is being handled with immense care. Staff meticulously photograph and scan fragile manuscripts, page by page. These ancient texts, some dating back hundreds of years, hold a trove of knowledge that scholars confirm exists nowhere else on Earth.

Thirteen years ago, when militant fighters linked to al-Qaeda seized the city, the institute staff and local families undertook a heroic, clandestine mission. They successfully smuggled tens of thousands of these priceless manuscripts south to the capital, Bamako, to save them from destruction. Now, after a dedicated effort that included extensive digitization, the majority of the collection has finally returned home.

A Unique Repository of West African Knowledge

Dr. Mohamed Diagayaté, the general director of the Ahmed Baba Institute, emphasized the singular importance of the collection. “You have a lot of historical information about the area,” he explained,

“like the Macina region, Mopti and its surroundings and Timbuktu and its surroundings. So, what we find in these ancient manuscripts cannot be found anywhere else.”

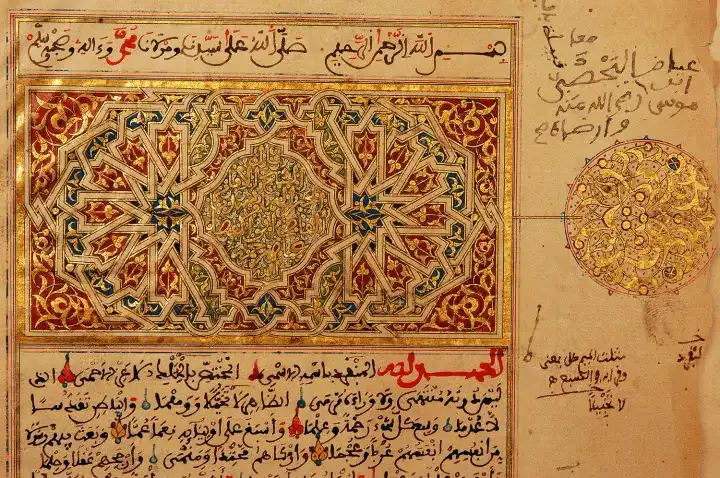

Within the institute’s display rooms and storage vaults, manuscripts lay open for preservation. Some texts bear the scars of the 2012 occupation, their edges blackened by fire damage, yet the writing remains clearly visible. Other manuscripts remain missing, their absence marked only by labels on empty shelves.

The collection is incredibly diverse. It features medical texts, intricate legal rulings, personal letters, astronomical notes, and detailed chronicles of powerful West African empires.

Scholars find debates documented within the pages, such as discussions on the morality of smoking tobacco or official decrees urging the reduction of dowries to help poorer men marry. Marginal notes quietly record local events and earthquakes long forgotten by external history.

Challenging Assumptions About the Past

Sane Chirfi Alpha, a founding member of SAVAMA DCI—a local organization dedicated to safeguarding and promoting the Timbuktu manuscripts—believes the collection reveals an intellectual depth that challenges common assumptions about the region’s past.

He offered a remarkable example: “According to old documents, there were doctors here in Timbuktu who performed surgery to treat cataracts.” He continued with a fascinating historical claim:

“The same manuscript also says that a doctor from Timbuktu saved the French throne. The crown prince was sick, and French doctors could not cure him. It was the doctor from Timbuktu who cured him.”

However, many manuscripts still reside within family libraries across Timbuktu, carefully preserved in traditional wooden chests. Some of these families face severe financial hardship, raising worries about the risk of private sales. Alpha confirmed the danger:

“The families that hold the manuscripts are in a difficult situation and receive no support. So, when these families have money problems, the father might want to sell the manuscripts.”

Perseverance and The Future of Scholarship

Inside the institute, staff tirelessly continue their work of cataloging, preserving, and educating. A crucial tradition documented in many texts is the “chain of teaching,” which meticulously recorded the lineage of scholars across generations.

Dr. Mohamed Diagayaté explained the tradition: “When a student finishes studying with a scholar, that scholar gives him a certificate saying he has taught him a subject, which the student has mastered.” He added, “The certificate also says that the student learned it from a certain scholar, and that this scholar learned it from another scholar, going right back to the person who wrote the original document.”

New specialists are actively being trained. Twenty-four-year-old student Baylaly Mahamane is dedicated to the cause. Mahamane said: “I want to be a manuscript specialist because I think it’s a good thing. When I become a manuscript specialist, I will be able to do many things that will benefit me and others.” He pointed to the practical knowledge within the texts: “Manuscripts contain lots of information about medicines and explanations of how to use them to treat various illnesses.”

The Journey Still Carries Risk

Despite the return of the institute’s collection, security remains a paramount concern. Some international researchers are still reluctant to travel north. Timbuktu is located in a region where armed groups linked to al-Qaeda and other militant factions remain active. Periodic attacks and road blockades make movement unpredictable and dangerous.

For many scholars, the physical journey to the city still involves unacceptable risks, severely slowing down essential research and preservation work that requires expert presence. Abdoulaye Cissé, the general secretary of the institute, noted:

“Some people are still afraid because they think it’s not safe in the north of Mali. This fear often stops them from coming here to do the work they need to do, which is related to the manuscripts.”

Beyond the institute’s walls, the city prepares for Mawlid al Nabi, the celebration of the Prophet Muhammad’s birth. Residents are hanging colored lights around Sankoré Mosque, a powerful reminder of the city’s long tradition of scholarship.

For many locals, the ancient manuscripts are integral to this lineage. They view the texts as part of the cultural fabric that has defined Timbuktu for centuries, connecting religious life, community heritage, and learning across generations.

As conservation and training advance, caretakers stress the current priority is to secure this vital written record of West African history and ensure its permanent accessibility for future scholars.

Bumrah’s Patience Pays Off: 5-Wicket Haul Sinks South Africa